Pictured above: (San Francisco 2020, after the labor day fires)

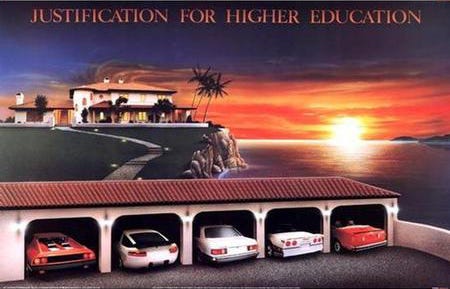

When I was 4 years old, my dad brought home a painting of an oceanside mansion with a fully loaded 5 car garage and the title "Justification for higher education" overhead. When you look at the painting it seems pretty obvious what the definition of education is given the context. And you know what, in the early 2000s I wouldn't be surprised if there was a strong correlation between advanced degrees and financial success - after all, this is well before student loan officers started asking if I was an organ donor or not. This same painting has remained above my desk for as long as I can remember, however I'm not sure if the same correlation can be said about me...

"Chris, your score was a lot like the weather this winter, well below zero".

...

Nice.

Two decades of staring at this painting and I see it differently now. Like what would the ocean view look like with a nice hefty oil rig in the middle? Or what about a nice post-apocalyptic orange hue like the image of San Fran above? Plastic bags whistling in the wind (not the Katy Perry kind), or dead marine life washed up ashore. Anyways, I digress. Even though the image itself can't change, my definition of the quote "Justification for higher education" has, especially as I've embarked on my journey in climate.

Picture above: (Actual copy of the painting above my desk)

You see, one of the biggest issues when it comes to climate change is the education part. In terms of science, the study of climate can be considered a relatively new area, leaving it susceptible to widespread misinformation, ignorance, complexity, and lack of education for the masses. All of which, also happen to be the reasons I've decided to start this blog. But there's one other aspect I've found really interesting as I think about how we talk about climate change.

And that's the psychology of communication.

To summarize, the way we communicate climate change can have a significant impact in the way people perceive it. Climate-topics are often grouped in with similar rhetoric as dooms-day events, apocalypse, and world-ending affairs. This psychologically changes the way we see the situation, giving it a "cliff or tipping point" effect, meaning we don't see climate change as a threat unless/until we see some catastrophic event take place that directly impacts our lives. Although many recent climate events could be considered catastrophic, the reality is that it only effects the vast majority of people through seeing it on the news, while the communities most susceptible face the destructive consequences.

- To quote Dorothy Fortenberry, Exec producer of Apple TV Show Extrapolations, "Things can be quite bad while you still go to work, you still watch TV, you still do the crossword puzzle, you still live your regular life. If you say climate change equals the total collapse of everything, then any moment short of the total collapse of everything must not be climate change". I'm more of a Wordle guy myself, but well-said Dorothy.

"But Chris, you yourself often refer to climate change as the end of the world".

You're right, and to be honest there is still truth to that. The reality is that we don't know the extent of damage that can be caused by destabilizing our climate and exacerbating our natural resources. It's more than likely climate change will take on a gradual effect - where community-engulfing wildfires, hot-girl summer heat exhaustion, and hurricane Oppenheimer all become normalized.

Or you know what, picture this:

Its the summer of 2002 and you're a kid in Dallas, TX. Your days are spent without a worry in the world, playing outside with your friends, running through sprinklers, playing fetch with your dog, only to come back inside at the end of the day for dinner.

- The average temperature in July 2002 was 83 degrees

Now imagine, its the summer of 2022 and you can't let your kid go outside because the heat index just broke a record at 109 degrees and you want to keep them safe.

- The average temperature in July 2022 was 92 degrees

Now imagine its a year later, July 2023 and Dallas just broke a new record high heat index at 110 degrees.1

Climate change may not result in an apocalyptic movie scene where the Earth splits in half and everyone runs around screaming, but it very well may manifest itself in other ways, like; not being able to travel to new cities because air quality is unbreathable, losing your home due to previously unforeseen weather disasters, or shortages in certain foods because agriculture can no longer thrive in its traditional form.

The way we talk about and educate others on climate has to reflect the severity of the problem without falling into the "out of sight, out of mind" phenomenon. 2050 goals and a commitment to not exceeding more than 2 degrees of warming are great, but the more we can relate the small impacts and threats to people's daily lives, the more successful we may be at providing real agency to solving the crisis.

And as for 4 year old Chris, I think he'd be proud of this new pursuit, of a justification for a higher education, except this time - for a better world.

Sources: Bloomberg, Breakthrough Institute, Weather.gov

This example is technically true, however a more accurate representation would be comparing a consecutive grouping of past years to a consecutive grouping of recent years to better understand how highs and lows continue to increase and become more severe. Annual temperature changes fluctuate by default, but we can understand warming by studying how temperature highs and lows shift over time. ↩